Develop with Cocoa for Apple Devices without using Objective-C

Summary

In this post I’ll go into detail about how, during my contracting work for Shimmer Industries (a company founded by Eskil Steenberg which is focused on developing a real-time lighting designing software), I worked on a piece of software which enabled us to use the MacOS and iOS APIs using a custom C API without having to use ObjC.

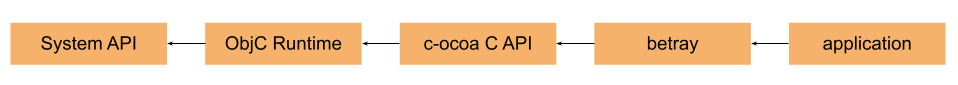

This technology (which we decided to call c-ocoa) was used to implement support for OSX & iOS for Eskil’s platform abstraction library betray. Betray is what’s driving the tools of Shimmer Industries. This allowed us to easily ship existing applications to mobile with only minimal code changes.  Abstraction layers of betray using c_ocoa for calling native APIs

Abstraction layers of betray using c_ocoa for calling native APIs

Eskil was generous enough to allow me to write about how this problem was solved. Additionally, we decided to make the final project completely open-source!.

The result of the endevaour is effectively a C-API which you can use to interact with the Cocoa API. Since there are C bindings for virtually all programming languages out there, you could even use the generated API with

- Lua

- Python

- Ruby

- or even Javascript

Yes, that’s right. Cocoa from the web, y’all!

In the end we have an application that shares 95% of it’s code between platforms and has an identical look and feel.  Application running on Android, Windows 11 and iOS

Application running on Android, Windows 11 and iOS

Since this is a code generator, another nice bonus is that you can immediately re-generate the C-API when a new ObjC API becomes available. There’s no waiting for the maintainer of a language bindings library to update the code, just re-run the generator and voila, you have the latest API.

Watched the latest WWDC where a new library got presented and want to try it out in your C-only program? Just re-generate and start tinkering!

“Why would you do this? Just use Objective-C!!!11”

Let me start this post by saying that yes, we could’ve used ObjC to be able to use the MacOS and iOS APIs from within the C codebase that was already in place. We decided against it though, because we wanted to have a pure C codebase without any of the weird ObjC code in there. We didn’t want maintainers (who are all mostly familiar with C) to first learn how to parse ObjC and also thought that this would be a cool thing that might also interesting other developers. It was certainly an interesting experience for me since outside some courses in University, I’ve never touched an OSX or iOS development and was also unfamiliar with ObjC and XCode as an IDE.

Introducing the Objective-C runtime

Eskil actually gave me the first hint by pointing me towards the ObjC runtime.

Quoting the official documentation it states that “The Objective-C runtime is a runtime library that provides support for the dynamic properties of the Objective-C language”. This sounds interesting, but slighty vague, so after taking a closer look at the documentation and the API itself, to see if there’s stuff in there that could be of use for solving this problem, I was delighted to see that there’s stuff like “give me a list of all classes and methods” and, most importantly “call the function with a given name on this object”. Bingo, this is exactly what I was looking for and seems to be a good foundation to build a C API on. Even better: The ObjC runtime itself is even a pure C API!

The plan

The overall plan is to have a C API which, under the hood, uses the ObjC runtime to call functions that are normally only accessible when programming in ObjC.

In praxis this would mean that ObjC code like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

char* getClipboardString()

{

UIPasteboard pasteBoard = [UIPasteboard generalPasteboard];

NSString pasteBoardContent = [pasteBoard string];

NSUInteger length = [pasteBoardContent lengthOfBytesUsingEncoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding];

char* pString = (char*)malloc(length);

[pasteBoardContent getCString:pString maxLength:length encoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding];

return pString;

}

could be written like this in C:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

char* getClipboardString()

{

uipasteboard_t pasteBoard = uipasteboard_generalPasteboard();

nsstring_t pasteBoardContent = uipasteboard_string( pasteBoard );

unsigned long length = nsstring_lengthOfBytesUsingEncoding( pasteBoardContent, NSUTF8StringEncoding );

char *cStr = (char *)malloc(sizeof(char) * (uint)length);

nsstring_getCString(pasteBoardContent, cStr, length, NSUTF8StringEncoding);

return cStr;

}

It was clear pretty early on that we’d need some kind of external code-generation tool that would use the ObjC runtime to parse the ObjC APIs and use the parsed information to generate the C API.

The code generator

Let’s get right into it and talk about the code generator. From a birds-eye-view the code generator is a command-line tool (written in C) which uses the ObjC runtime API to query various data from ObjC APIs and uses this queried data to generate multiple .c/.h files which can be used in a project to interface with these ObjC APIs using normal C functions.

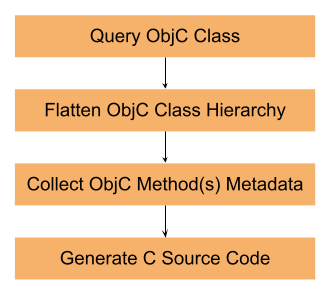

For each ObjC class that you want to create a C API for, the tool basically does these things in order:  Code Generator Workflow

Code Generator Workflow

Query ObjC Class

The first step is to query metadata about the class that we’re interested in turning into a C API. The code generator works by providing it with one or more ObjC class name(s) (optionally including wildcards). For each class the generator generates a pair of .c/.h files.

This is done by first querying for all (see notes about what all actually means) available classes using objc_getClassList(). The query results will be returned using an opaque type Class which can be used together with class_ prefixed functions to query more metadata about a specific class. So the generator first caches all available classes (I’ll later talk about how classes are made visible for the ObjC runtime API) and then compares the name of each class (by using class_getName()) against the input of the user.

Once one ore more matching classes have been found, we move to the next step.

Note: All available classes depends on what ObjC frameworks are linked at the time the code generator is run. This also means that you can’t generate code for iOS only classes when running the code generator on OSX since you can’t link the iOS frameworks to the OSX app. For generating code for iOS classes, you have to run the code generator on an iOS simulator.

Flattening ObjC Class Hierarchy

ObjC is an object oriented language, C is not. So we need some way to map ObjC’s “object orientness” to C functions.

For this problem I decided to flatten the class hierarchy of the class that you want to export to C. This is done by using the class_getSuperClass() function from the ObjC Runtime API - this also returns an object of type Class - same as objc_getClassList() before.

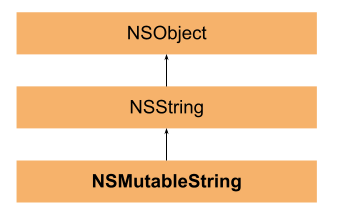

For each class found during the “Query ObjC Class” step, the program needs to recursively move up the class hierarchy, This is an image illustrating the class hierarchy for the class NSMutableString:  Class Hierarchy of NSMutableString (The arrow point upwards the class hierarchy)

Class Hierarchy of NSMutableString (The arrow point upwards the class hierarchy)

Unlike C++, ObjC does not support multiple inheritance (thank god!), so this process is rather straight-forward.

By using class_getSuperClass(), we can recursively go up the class hierarchy and query the methods of each individual class. Querying the methods of a class is done using the class_copyMethodList() API - this returns an array of the opaque type Method which can be used to query metadata about a specific method.

The result of this step is an array of methods from the complete class hierarchy. Spoiler: Since we’ll later call the methods using just their name, we don’t have to worry about methods that have been overriden at this point.

Note: This works for only for non-static methods. To also get the static methods of a class you have to get what’s called the

meta-class. This is done by using theobject_getClass()function with aClassobject as it’s argument. This returns another object of typeClass. This object can be used together withclass_copyMethodList()to get the list of static methods.

The result of this step are 2 arrays:

- Array of all static methods

- Array of all non-static methods

Resolving ObjC Runtime Types

Before talking about how the metadata of methods is queried, I have to talk about how types are encoded in the ObjC runtime.

When querying argument and/or return types using the ObjC runtime you “only” get back a string. Naively I though that this is just the name of the return type (eg: int, float or NSString) but things are a bit more complicated than that. Basically we have to differentiate between base types (int, char, float etc), user defined POD(plain-old-data) types (your typical structs), references (pointers) and ids (more on that later). For each of these types, the type name from the ObjC runtime has to be parsed differently.

Base Types

Let’s start with the most simple - base types. Instead of fully qualified type names (like int), the ObjC runtime returns a string with 1 element. Fortunately, there’s a 1:1 mapping between these “ObjC base types” and “C base types”. The mapping listed below is from the objc/runtime.h file

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#define _C_CHR 'c'

#define _C_UCHR 'C'

#define _C_SHT 's'

#define _C_USHT 'S'

#define _C_INT 'i'

#define _C_UINT 'I'

#define _C_LNG 'l'

#define _C_ULNG 'L'

#define _C_LNG_LNG 'q'

#define _C_ULNG_LNG 'Q'

#define _C_FLT 'f'

#define _C_DBL 'd'

#define _C_BFLD 'b'

#define _C_BOOL 'B'

#define _C_VOID 'v'

User defined structs

The next type, user defined POD types (struct XY) are a bit more complex. The ObjC runtime returns the type name and the complete layout of the custom type. To drive home what I mean by this, think of a struct like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

struct AwesomeType

{

char a;

int b;

float c;

};

This type would be encoded by the ObjC runtime like this: {AwesomeType=cif} With the info on how base types are encoded, the part after the equal sign can be parsed as a list of base types. So this is basically AwesomeType = char int float.

This extends to structs within structs as well. So this struct:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

struct Foo

{

int a;

unsigned int b;

float c;

};

struct Boo

{

double a;

Foo foo;

};

Would result in this type name for struct Boo: {Boo=d{Foo=iIf}}.

Note: The first version of the code generator actually re-created all structs that where used as return and argument types but as you might already have guessed, you loose the member name of each struct member. The current version assumes that you use the actual ObjC struct (which are the same as C structs).

References

Following this, we have references which are marked with a ^ preceeding the encoded type name. This is thankfully quite easy to incorporate into the existing type parsing. Care should be taken with opaque types however since they’ll be returned like this: {OpaqueType=} (For reference: Opaque types are types where the caller doesn’t know the type layout).

ID

Finally, we have id - this is actually a type from the objc runtime API. This is a reference to an ObjC object, unfortunately for this we don’t get any more type information. Looking at this from C, we basically only know that this is a void* and not what type.

Collect ObjC Method Metadata

Now that it is established how the types are encoded, we can continue with querying metadata about each individual method.

After the class hierarchy has been flattened, we have generated a list of all methods of the complete class hierarchy. In this step we use this list to query information about each individual method. Things that we’re interested in include the following:

- Method Name

- Return Type

- Number of Parameters

- Type of Parameters

Since we now operate on objects of type Method, we can use the ObjC runtime functions prefixed with method_. The first function that is being used is method_getName() - this is similar to class_getName() and returns a string.

The next function that we can use is method_getReturnType() this returns an ObjC runtime encoded type string (that we know how to parse thanks to the previous chapter). To get the parameter list, method_getNumberOfArguments() together with method_getArgumentType() can be used. The returned type is also encoded as an ObjC runtime type.

Note: Unfortunately the name of the arguments can not be queried - until this is solved, the arguments follow a

arg0,arg1,arg2, etc naming-scheme.

With these information available, we have a complete function signature and now only need to find out how we can do the actual function call.

Calling ObjC Methods Using The ObjC Runtime

For calling ObjC methods various variations of objc_msgSend can be used. I say “various variations” because there are multiple version depending on what kind of return value you expect (this only applies when targeting i386 hosts).

-

objc_msgSendfor function that return types <= 16 bytes. -

objc_msgSend_fpretfor float return types. -

objc_msgSend_stretfor functions that return types > 16 bytes.

Calculating the size of the return type can be added as part of the pass where the return type is parsed. During code generation, the size and type of the return value can then be used to select the correct objc_msgSend function.

If you look at the definition of any of these function, you’ll see that the first 2 arguments are always ID self and SEL selector. The first argument ID self is a pointer to the object which we want to call this method on (or, in case of static methods, the meta-class). The SEL selector argument is the name of the method at runtime. This can be retrieved by calling sel_registerName() with the method name as argument (as given by method_getName()).

Note: The return value of

sel_registerName()is cached internally.

Generate C Source Code

We’re now perfectly set-up to start generating the C source code, which will become the basis of our API.

If you remember from the previous chapter we are left with 2 arrays which contain elements of type Method after the class hierarchy has been flattened. One array for static and one array for non-static methods. These arrays are now used to create matching C functions for each individual method.

We do this by using the method meta-data that we’ve collected earlier. The result of this step will be matching .h/.c files for each ObjC class that should be exported.

The first step when writing the C source files is always the file prefix. For .h files the prefix is a header guard and a single typedef for syntactic sugar (example for NSString):

1

2

3

#ifndef C_OCOA_NSSTRING_HEADER

#define C_OCOA_NSSTRING_HEADER

typedef nsstring_t void*;

(for .h files there’s also a postfix needed to add the #endif for the header guard).

For .c files this is a couple of defines that change what variation of objc_msgSend is being called based on the target ABI (since this could theoretically be x86 or ARM). To make the generated C code work on both architectures, these defines are added at the beginning of every .c file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

#ifdef __arm64__

#define abi_objc_msgSend_stret objc_msgSend

#else

#define abi_objc_msgSend_stret objc_msgSend_stret

#endif

#ifdef __i386__

#define abi_objc_msgSend_fpret objc_msgSend_fpret

#else

#define abi_objc_msgSend_fpret objc_msgSend

#endif

Note: this means that instead of

objc_msgSend_stretandobjc_msgSend_fpretwe need to useabi_objc_msgSend_stret&abi_objc_msgSend_fpretrespectively.

For each C function we first call sel_registerName() to get the correct selector for the method that we want to call. After that we have to make the call to objc_msgSend() to perform the actual function call.

Note: Since all the

objc_msgSendfunction are typless, they need to be cast to the correct function-ptr type to be called with the correct arguments. This will be done using a “synctactic-sugar” helper-macro for better readability and debugability.

Example

To give a concrete example let’s focus on the source code generation of the NSString class with one method, getCString()

The function declaration in Objective-C for that function looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

@interface NSString : NSSObject

- (BOOL)getCString:(char *)buffer

maxLength:(NSUInteger)maxBufferCount

encoding:(NSStringEncoding)encoding;

@end

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Usage-Code:

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

NSString* string = [[NSString alloc] init];

//Fill string with data...

//..

char buffer[512];

[string getCstring:buffer maxLength:512 encoding:NSUTF8StringEncoding]

}

Using the information provided earlier, the generated c_ocoa .h/.c file(s) would look like this (including usage-code):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// nsstring.h

#ifndef C_OCOA_NSSTRING_HEADER

#define C_OCOA_NSSTRING_HEADER

typedef nsstring_t void*;

bool nsstring_getCString( nsstring_t object, char* arg0, unsigned long long arg1, unsigned long long arg2 );

#endif

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// nsstring.c

#include "nsstring.h"

bool nsstring_getCString( nsstring_t object, char* arg0, unsigned long long arg1, unsigned long long arg2 )

{

SEL methodSelector = sel_registerName( "getCString:maxLength:encoding:" );

#define nsstring_getCString_call( obj, selector, arg0, arg1, arg2 ) ((bool (*)( id, SEL, char*, unsigned long long, unsigned long long ))objc_msgSend) ( obj, selector, arg0, arg1, arg2 )

return nsstring_getCString_call( (id)object, methodSelector, arg0, arg1, arg2 );

#undef nsstring_getCString_call

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Usage-Code:

int main(int argc, char** argv)

{

nsstring_t string = nsstring_alloc( nsstring_init() );

//Fill string with data...

//..

char buffer[512];

nsstring_getCString(string, buffer, 512, NSUTF8StringEncoding);

}

Conclusion

Generating a pure C API to interface with the OSX/iOS system APIs was a very interesting problem for me personally since it gave me an excuse to work with ObjC and get to know some internals of the language. This was definitely a big undertaking and, to be honest, I expected it to fail at any moment because of some problem(s) that we didn’t foresee. But fortunately everything worked out pretty nicely and it was definitely a scary feeling letting the generator work through the entire class hierarchy of big frameworks like AppKit, Foundation or GLKit. That being said we did hit a couple of problems that we’re actively working on, namely parameter naming and adding auto-generated documentation to the various functions. But all in all the result is pretty cool and we were able to ship an iOS application using the technology.

Sourcecode

The entire source code of the code generator has been made open source and can be accessed on github. Follow the README in the repository to build the generator locally.