Multithreading in games - Comment on 'Parallelizing the Physics Solver' BSC 2025 Talk

This blog post was inspired by watching Dennis Gustafsson’s 2025 BSC talk “Parallelizing the Physics Solver”.

You don’t have to watch the video to follow the content here. In short, he describes the challenges he faced in using multithreading to speed up the physics solver of the Windows PC version of his excellent game Teardown.

I really liked the talk since it’s a great example of someone using profile-guided-optimization to improve the performance of a slow piece of code.

There are just a couple of things I like to comment on.

To keep this post focused, I’ll assume the reader knows what a job system (aka task scheduler) is, in short: it’s a system where you submit a bunch of isolated jobs, which are then scheduled onto worker threads that run in parallel.

All your cores are belong to us

Every gamedev ever when they start to design a new job system

Every gamedev ever when they start to design a new job system

One thing that I immediately noticed is that the job system that Dennis presented is basically trying to use the whole CPU - meaning that the system is scaled to ideally utilize every CPU core available (except one). I’ve seen that behavior with many job systems I’ve looked at and I’m guilty of doing the same thing when I worked on a job system at a previous job.

At it’s core, many implementations look like this:

1

2

3

JobSystem* pJobSystem = createJobSystem();

const int workerThreadCount = GetActiveProcessorCount(ALL_PROCESSOR_GROUPS) - 1;

pJobSystem->spawnWorkerThreads(workerThreadCount);

Where JobSystem::spawnWorkerThreads() spawns N threads, where N equals the return value of GetActiveProcessorCount(ALL_PROCESSOR_GROUPS) minus one, since, as Dennis correctly states, you don’t want to hog all the cores. Leave at least one CPU core for the OS and other apps.

Note: The open-source task scheduler EnkiTS by Doug Binks, which I’ve seen used in several games, also defaults to this behavior if you use

enkiInitTaskScheduler()orenki::TaskScheduler::initialize()without specifying a thread count.

This seems logical at first: it scales with core count, ideally assigns one worker per core, and minimizes cache coherence issues. Win-win, right?

Unfortunately, reality isn’t that simple. Windows and/or the hardware will most likely interfere in the name of efficiency and depending on your workload, trying to utilize all the cores will actually reduce your overall performance, as counter-intuitive as this may sound like.

To understand why that is, we have to consider the underlying hardware.

P-/ vs E-Cores

The performance measurements that are shown during that presentation were taken on an i9-14900F Intel CPU, which is a hybrid CPU1. In practise, this means that the CPU has 2 or more different cores that it’s using to execute instructions. For this concrete CPU, there are 2 different cores: Performance cores and Efficience cores (commonly referred to as P-& E-Cores), with the general, overdramatic, consensus being that P-Cores are fast and awesome and E-Cores are slow and lame. While the E-Cores are slower, it’s not “half of the performance of the P-Cores”, as was stated during the talk.

In fact, looking at the specs for that particular CPU, in terms of base clock speed, the E-Cores are around 75% as fast as the P-Cores.

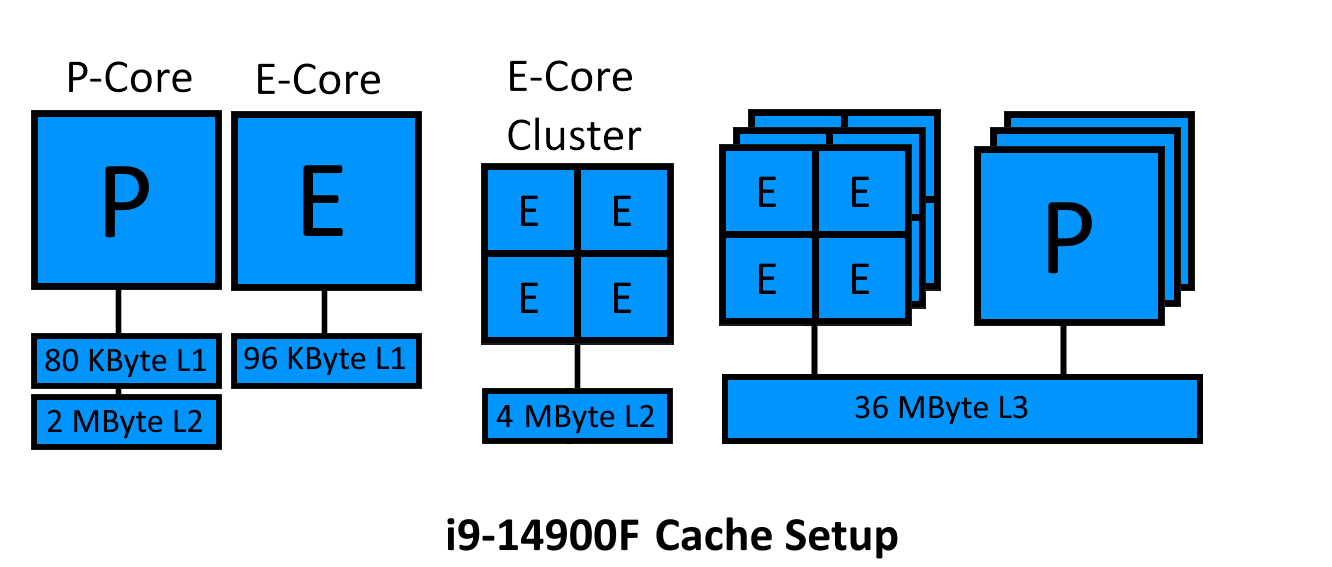

For completeness, we also have to consider the cache-setup of P-/ and E-Cores since there a quite a few differences.  i9-14900F cache setup

i9-14900F cache setup

From this hastly-thrown-together image we can see that, for an i9-14900F, each P-Core has 80KB of L1, which is little bit less than the E-Cores 96KB of L1. An E-Core cluster, consisting of 4 E-Cores, shares one 4MB L2 Cache where as each P-Core has it’s own 2MB L2 Cache. Finally, all cores share a 36MB L3 cache.

The Windows scheduler assigns threads to run on CPU cores. Ideally, we want threads to run on P-Cores, if they are available. On Intel CPUs, the following priority system decides which CPU core to run a thread on:

- Run on P-Core, if no P-Core is available,

- Run on a single E-Core within an E-Core cluster (to minimize the contention on the shared L2 cache of the cluster), if there’s not a single E-Core available in a cluster,

- Run on an E-Core within the lowest utilized E-Core cluster, if all E-Cores are utilized,

- Run on P-Core SMT.

So, depending on your workload, if you’d actually utilize all your cores, you could run into a scenario where the E-Cores within an E-Core cluster will trash each other’s cache. Additionally, Windows will monitor the utilization of CPU cores and eventually it’ll park CPU cores that it feels are underutilized. Core Parking is a power saving mechanism within Windows to not waste power on CPU cores that aren’t doing anything. While in theory this is a good thing, the parking and unparking of cores does come with a slight performance hit, especially if this is done over and over again within a single frame.

Note: Core Parking is an optional feature which is turned on by default for the balanced & power saver power plans in Windows. I’ve seen many threads in the Steam Community, Reddit, etc suggesting to turn this off but if you want to ship a game on Windows I’d assume only the enthusiast go the “extra mile” of actually disabling this, meanining that you still unfortunately have to account for this. The Laptop and Windows handheld gamers will thank you for it though ;)

Core parking issues are even more pronounced when threads are hard affinitized on individual CPU cores. If you consider code like this (taking our JobSystem::spawnWorkerThreads() from the previous listing):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

void JobSystem::spawnWorkerThreads(int threadCount) {

assert(threadCount < (GetActiveProcessorCount(ALL_PROCESSOR_GROUPS) - 1));

for(int i = 0; i < threadCount; ++i) {

HANDLE threadHandle = CreateThread(nullptr, 0, workerEntryPoint, nullptr, 0, nullptr);

mHandles[i] = threadHandle;

const DWORD_PTR threadAffinityMask = 1ull << i;

SetThreadAffinityMask(threadHandle, threadAffinityMask);

}

}

This pins each thread to one particular CPU core, which effectively means that the thread can only be executed on that core alone. If you consider a scenario where a thread is pinned on eg. Core#1 and becomes active, but Windows decided to park Core#1 because nothing was happening on that core for some time, Windows has no chance but to unpark Core#1, even if other cores would be available to run that thread, as it has to respect the hard affinity that was set using SetThreadAffinityMask().

The alternative of hard-affinitizing your thread is soft affinity, which is basically a hint to the Windows scheduler to say ‘hey, I would really like this thread to run on this class of CPU cores, but if you can’t do that, feel free to ignore my hint’. This is supported by the EcoQoS family of APIs or CPU Set family of APIs. EcoQoS is a hint that just differentiates between efficiency vs power. CPU sets are one level below where you can select a range of CPU cores for a given thread to run on (Windows will still ignore this if it can’t find a suitable core in that range during runtime). More over, the soft-affinity functions of CPU sets should be “core parking aware”, meaning that Windows won’t unpark a core if it can run on another core that’s within the range of CPUs you provided.

Note: While the official Intel recommendation for gaming performance is to use soft affinity over hard affinity, hard affinity can still be beneficial for selected use cases (ie: have a job system that only works on background tasks (tasks that don’t have to be finished by the end of the CPU frame) and hard affinitize the workers on E-Cores).

Implementation #1: Sync primitives — keep the cores awake!

But now lets focus on the content of the talk again. Based on the initial implementation shown in the talk, workers go to sleep as soon as the job queue is empty. If no other thread needs that core, the CPU enters a C-State. The deeper the C-State, the longer the wake-up time — and at certain levels, the core’s cache is flushed too. In that case, you’ll end up paying twice: once to wake the core, and again to repopulate the cache.

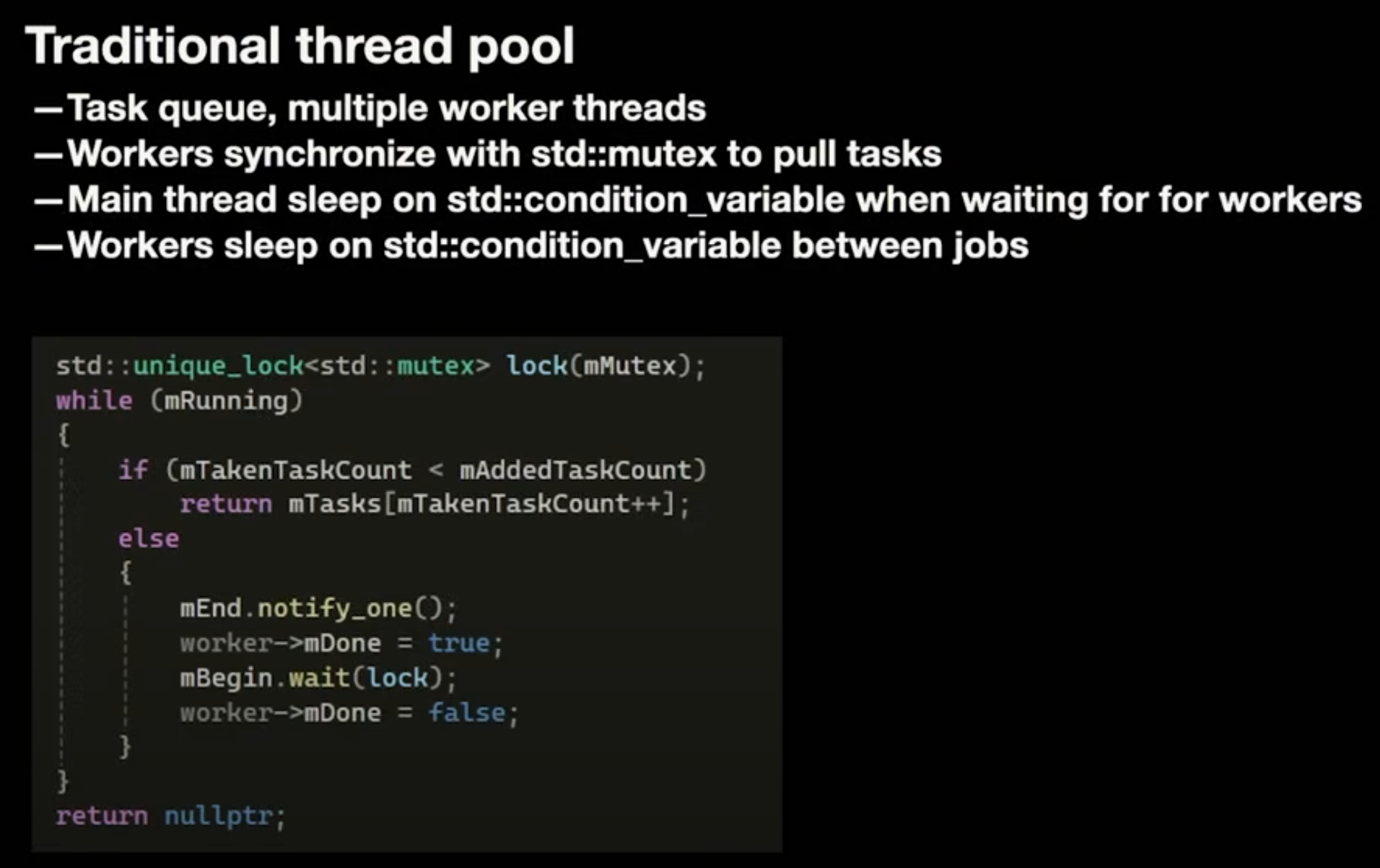

This effect is visible in the first implementation from the talk:

This implementation is somewhat lock-heavy but should be fine in certain scenarios. The main thread sleeps while workers are active, which is good, and the workers idle between job bursts.

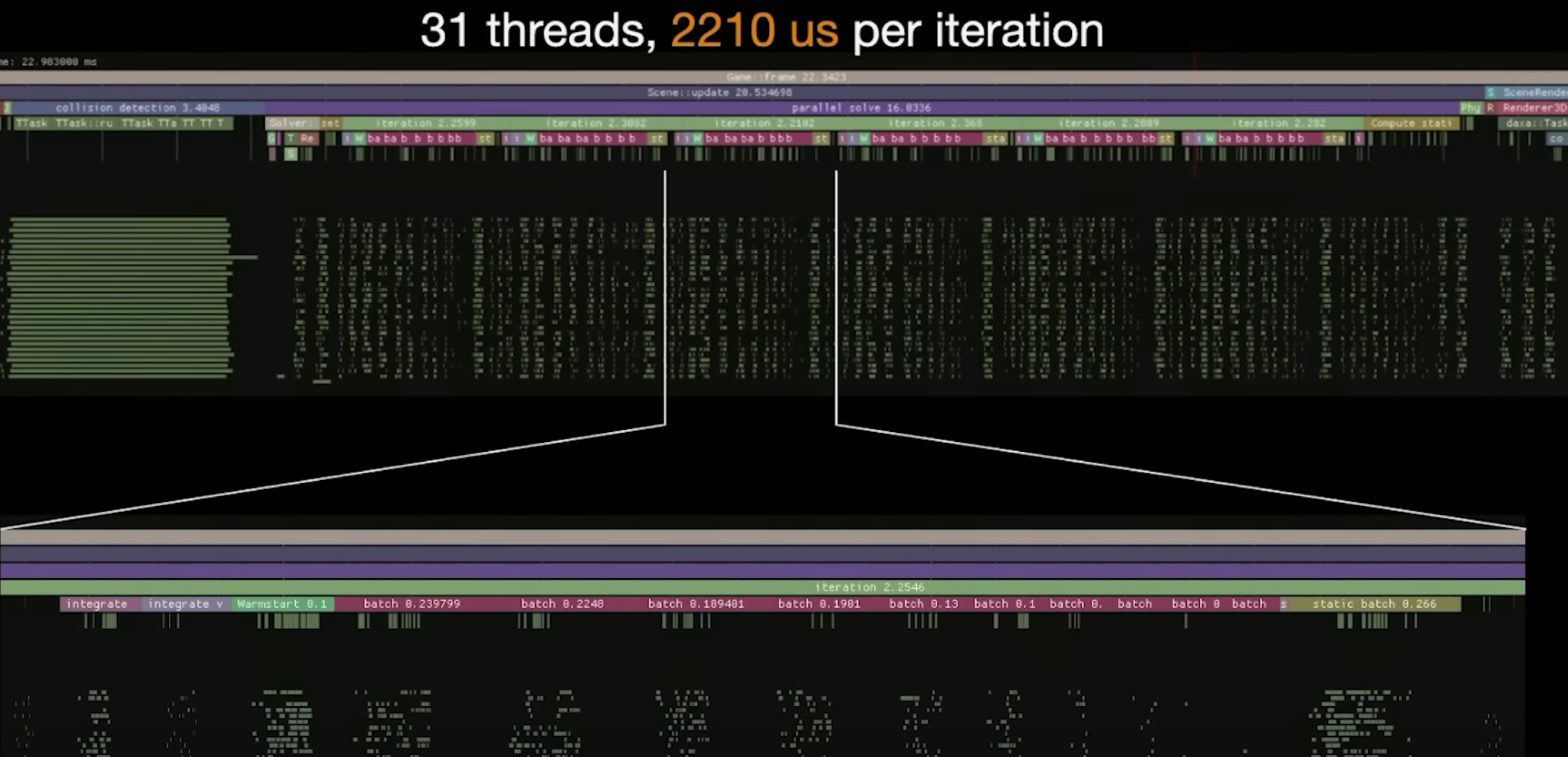

However, the profile tells a different story:  Too many cores, too little work

Too many cores, too little work

You can see gaps (bubbles) between jobs, caused by the mutex guarding the job queue. During these gaps, the CPU core may enter a C-State, only to wake up again shortly after - introducing latency.

Dennis correctly concludes that avoiding C-State transitions leads to a more responsive system. But there’s another point: this graph also shows that the per-job workload is too small.

Using the red batch bars as reference, each job seems to run for only a handfull of microseconds. At that point, the cost of the queue access outweighs the actual job cost. If jobs are working on isolated problems, consider batching multiple tasks per job. That way, workers stay busy longer, have to access the job queue less frequently and thus, sleep less often.

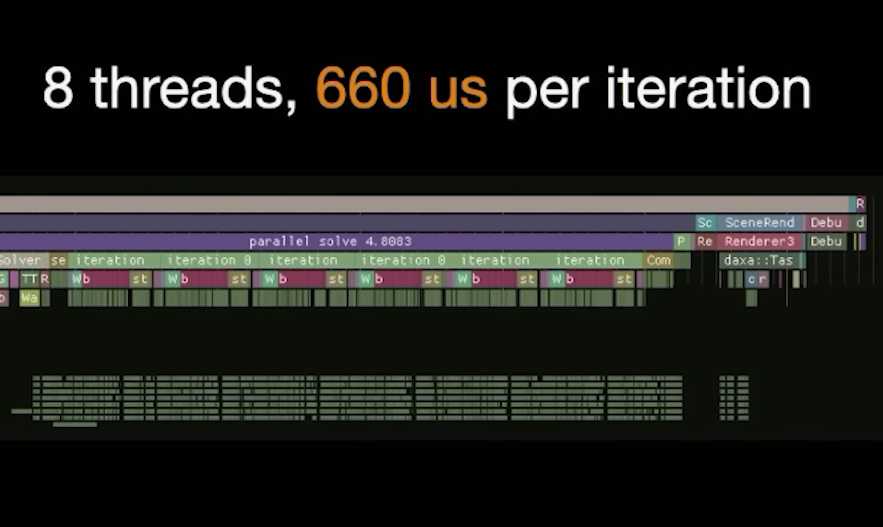

This is indirectly acknowledged by the decision to reduce the worker count to 8, which improved frame performance:  Less cores, better performance?!

Less cores, better performance?!

As Dennis points out, this likely limits execution to P-Cores only. He’s right that Windows favors P-Cores when scheduling. However, this accounts for only a tiny fraction of the performance gain. The bigger win comes from higher per-thread utilization.

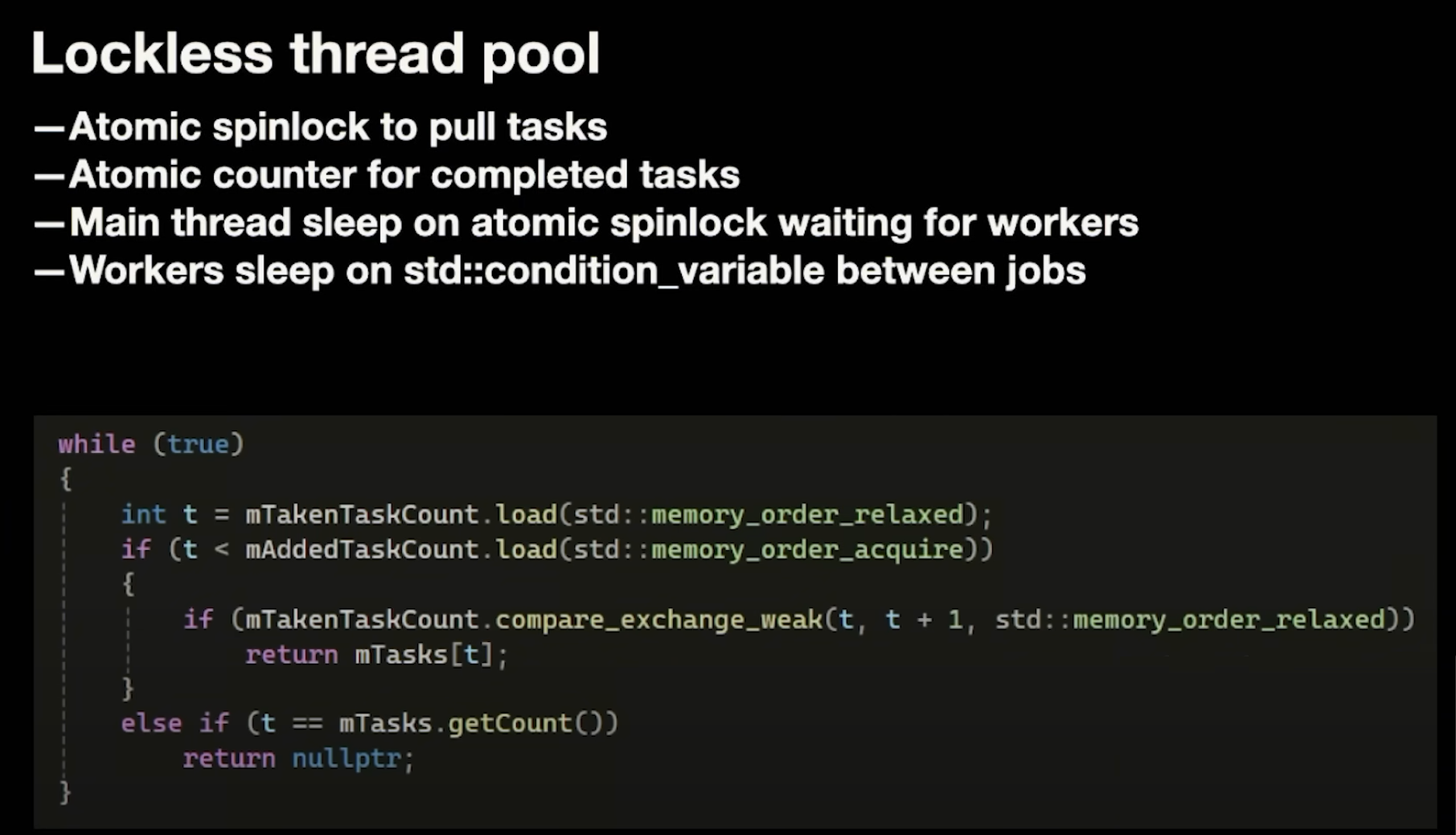

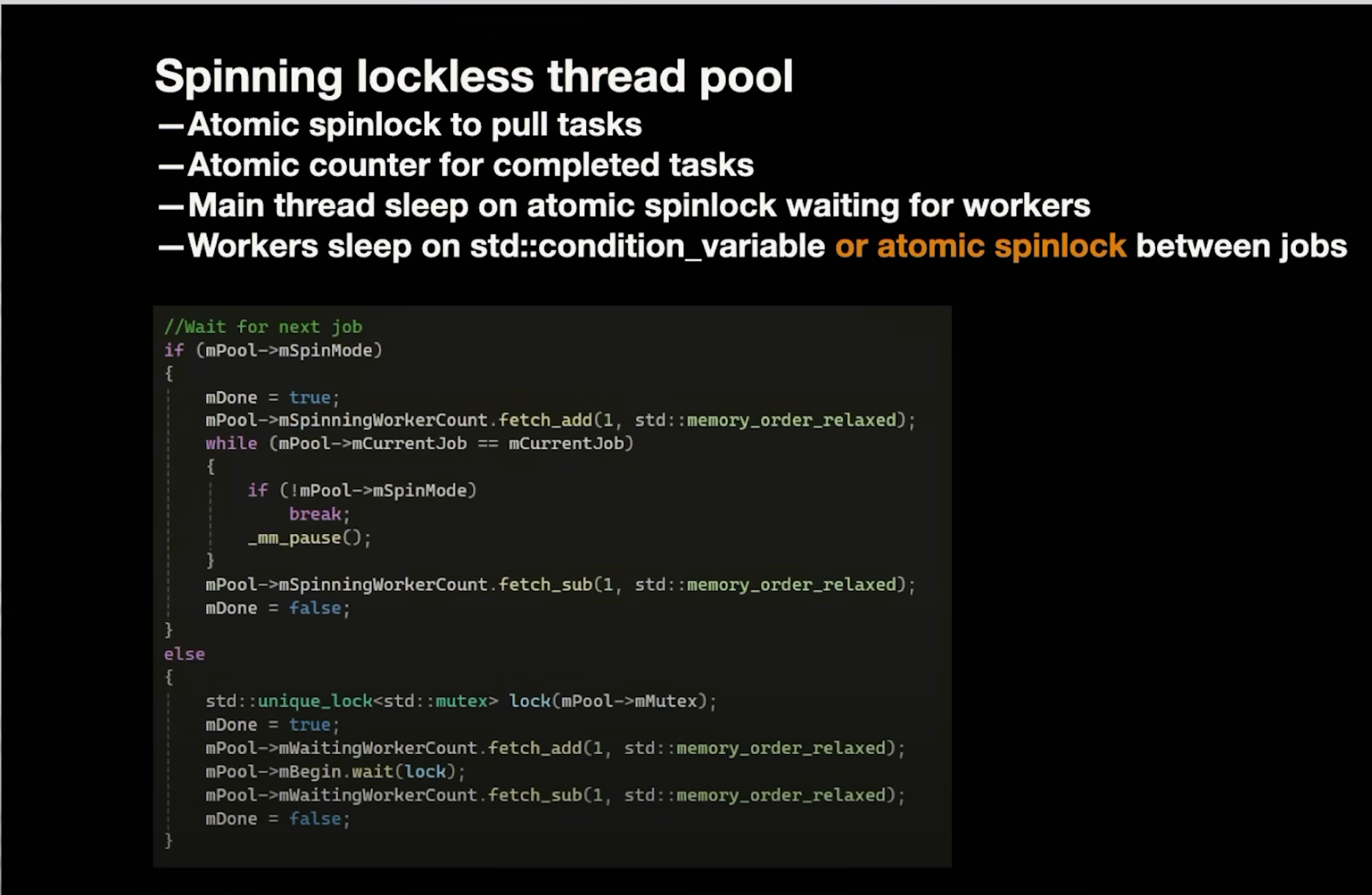

Implementation #2: Lockless thread pool — the burning core!

Dennis correctly identifies the issue of workers sleeping between jobs because of the high contention of the job queue mutex and switches to a spin-wait strategy to keep cores active until the work is done.

The code is pretty standard for a lockless job queue. But the statement “Main thread sleeps on atomic spinlock waiting for workers” is problematic because this means one CPU core (likely a P-Core) is just burning cycles in a busy loop.

I assume this is something like:

1

2

3

while (mFinishedTaskCount.load() < mTasks.getCount()) {

_mm_pause();

}

Note: I hope you’re using

_mm_pause()in your spin loops!

Surely, there are other things that the main thread could be doing. Two possibilities are:

- Let the main thread help execute jobs until the queue is empty, and only then enter a waiting state until all workers are finished

- Or actively put the main thread into a wait state until all work is done via something like

WaitForMultipleObjects(), each worker could set a windows event to notify the main thread when all work is finished, causing the main thread to wake up again. This would effectively free up the main thread’s core to be used by one of the workers (even allowing you to utilize one more worker thread!). Waking the main thread is also cheap, since the core that the main thread will eventually run on, is active.

Implementation #3: Spinning lockless thread pool - ideal state!

The final implementation (where workers never sleep) is well-suited to this kind of workload, aside from the main thread still spinning.

With this approach either the first implementation is used, where workers contest the mutex or workers are spinning forever. Workers always spinning is probably the ideal approach for the workload depicted in the profile graphs, namely super small jobs that frequently have to hit the job queue. Though I wonder if a hybrid of both would be even better.

The workers could spin up to a certain maximum and if, during that timeframe, there’s still no work in the queue, you can put them to sleep until work has been added. Or, to put this into code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

while(true) {

//spin until mMaxSpinCount is reached

for(int i = 0; i < mMaxSpinCount; ++i) {

if(mAddedTaskCount.load() > mTakenTaskCount.load()) {

break;

}

_mm_pause();

}

//sleep if no work has been added to the queue

if(mAddedTaskCount.load() == mTakenTaskCount.load()) {

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> lock(mPool->mMutex);

mPool->mBegin.wait(lock);

}

//try to get job from the job queue

while(mTakenTaskCount.load() < mAddedTaskCount.load()) {

int t = mTakenTaskCount.load();

if(mTakenTaskCount.compare_exchange_weak(t, t + 1)){

return mTasks[t];

}

}

}

Now, this all being said, Dennis did an awesome job optimizing his workload for multithreading and correctly deduced the various approaches to get out of the performance pitfalls he’s ran into. What I’ve written here are merely suggestions based on patterns I’m seeing in many job systems (including my own 😅).

This concludes this blogpost - if you agree/disagree or have comments, please get in touch with me

Many CPUs these days use a hybrid architecture, like ARMs big.LITTLE architecture, which is used by most modern phones + Apple silicon. ↩